The history of German-Muslim relations is long. The “Soldier King” Frederick William I had in 1732. Converted a riding stable to a mosque.

Statistically, Islam has been a part of Germany for long time. Muslims have been living in Germany for centuries, currently there are nearly five million of Muslims living in Germany. About fifty percent of them are German nationals. Most of them came from a migrants families that came from Turkey, Yugoslavia, Morocco and Tunisia. From 1961, the Federal Republic had signed recruitment agreements with these states. “We called for manpower and people came,” says Max Frisch.

So-called guest workers helped to rebuild Germany after the Second World War and made their contribution to the economic miracle in factories, at supermarket checkouts, in hospitals or on construction sites. But when the economic miracle ended, the West German industry first troubled and in 1973 a recruitment ban was issued, only a part of the migrants returned to their countries of origin. Around four million Turkish Muslims had immigrated under the terms of the recruitment agreement. At the 1987 census, about 1.3 million Muslim Turks and about 280,000 other Muslims were registered.

Less well known is the history of the very first Muslim migrant workers. They were soldiers. In 1731, the Duke of Courland gave King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia 22 Turkish guardsmen. Mostly prisoners of war, which were intended to reinforce Friedrich Wilhelm’s favorite unit, the guards regiment of the “Langen Kerls”. To sell or give away members of the military belonged in the Baroque to the customs of courtly power politics. The small Courland, located in present-day Latvia, was threatened by the great powers of Russia, Sweden and Prussia at the time and continued to favor the western neighbor for its continued existence. Duke Ferdinand was already connected to Prussia by his mother Luise Charlotte of Brandenburg.

The Prussian state idea was based on tolerance and discipline.

King Frederick William I, whose obsession for all things related to the military earned him the nickname “soldier king”, in 1732. for the new Muslim subjects in the Long Stable, he converted a hall to a mosque. This was the first mosque constructed on German soil. The prayer room has not survived, no picture of it exists. It was only a few steps away from the garrison church, which was to become a symbol of Prussian militarism and has been rebuilt since 2017.

The glockenspiel of the garrison church was regarded as the “heartbeat of Prussia”, for a time its sound mixed with the Muslim prayersongs. However, they were on Sundays, not on Fridays. “It was the wish of the king that God in Potsdam was worshiped in all tongues and in every faith of the earth at the same hour,” writes Jochen Klepper in his 1937 novel “The Father” about Friedrich Wilhelm. Therefore, the king “kindly asked” the Turks of his regiment whether “for their sake, Allah’s il-Allah!” Could not be “the Prussian Sunday morning for their Ottoman Friday.”

Tolerance and discipline, the Prussian idea of the state was based on these pillars. For the openness to strangers, spoke mainly pragmatic reasons, they should contribute to the increase in the Thirty Years’ War and then decimated population. Frederick II, later called “the Great”, continued the welcome culture policy of his father Friedrich Wilhelm. Immediately in his first year in office, the francophile ruler wrote in modest German a marginal note on a report by the General Directorate: “All religions are the same and continue to enjoy their care so that they can profit, and whom Turks and Gentiles will take and want the land Poeppling, so they want to build mosques and churches. “

Five Islamic newspapers, produced in the Reichsdruckerei

Even as mosques, Frederick II built barracks. Non-Christians were also welcome to his campaigns. In 1741, during the First Silesian War, a Muslim unit with 73 horsemen, dispersed from Russia, joined its army. From the young Tartar noblemen, so-called “Oghlanis”, the first Prussian lance troops were formed. Frederick’s cavalry general Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, who with his attacks in 1757 decided the Battle of Rossbach, had a white horse who heard the name “Mohammad”. The parents of the animal were called “Prophet” and “Fatme”.

In the Seven Years’ War, the “Tatar fright” became proverbial, coming from the Orient country, these cavalrymen were dreaded elite mercenaries. The name of the Prussian “Ulanen” regiments goes back to the Turkish-Tatar word “Oglan”, meaning the “son, young young man, soldier “. When 1807 Prussian troops defeated Napoleon’s army at Eylau,Muslim soldiers were among them. They wanted, as stated later in the reports, “their king for the safeguard of their ancestral form of life and the freedom of belief given to them to thank.”

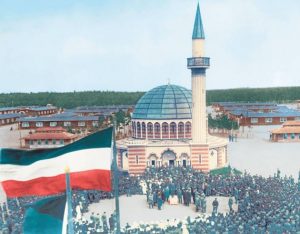

One hundred years later, soon after the beginning of the First World War in 1914, the German Reich signaled the construction of a mosque for the “Mohammedan prison camp” in Wünsdorf near Zossen. The red-and-white wooden building was built in the style of an orientalising historicism, its minaret towering over the landscape of the city of Brandenburg at a height of 23 meters. There were 4,000 prisoners of war in the model camp, especially Russians, Indians, Moroccans and Senegalese. Five Islamic newspapers were published, which were produced in the camp and in the Reichsdruckerei. The Empire wanted to win the favours of Muslims for a jihad against Russia, France and Britain in the Middle East. But that did not happen.

Comments