Following the collapse and disintegration of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba during the civil wars of 1009–1013, al-Andalus fragmented into about 20-30 kingdoms known as the party kingdoms, reyes de taifas or mulūk al-tawā’if. Some of these emirates, such as the Taifa of Silves, were little more than self-governing city-states while others, such as the Taifa of Seville, controlled large swathes of territory. Although there were three Taifa periods—the first from 1010 to 1110, the second from 1144-1172, and the third from roughly 1220 to 1270—I will be focusing this post on the first Taifa era, which is what scholars usually mean when they refer to the “Taifa Kingdoms.” I thought it would be useful to simply lay out the names and ethno-tribal origins of the ruling families of the various Taifa kingdoms in order to demonstrate the complex political situation that had arisen in 11th-century al-Andalus. Although the question of “ethnicity” is certainly a troublesome one in the medieval period (not least in al-Andalus!), the concepts of “Berber,” “Arab,” and “indigenous Iberian” (muwallad) were all deployed and utilized by various factions in the Taifa kingdoms during the 11th century. Rather than attempt any major analysis (I’ve provided a list of further reading for those interested in learning more), it seemed like a good idea to clarify the tribal and “ethnic” background of each of ruling families of the Taifa kingdoms.

It is quite notable (especially when one considers that they probably composed a significant majority of the Muslim population of al-Andalus) that only two very small kingdoms were actually of Hispano-Muslim (i.e. muwallad/muladí) origin, while the vast majority of the Taifas were ruled by various Berber dynasties who had migrated to al-Andalus during the late Umayyad period, especially during the regency of Ibn Abī ‘Āmir al-Manṣūr (d. 1002). It was these various Berber tribes, which played such an instrumental role in al-Manṣūr’s successful campaigns against the northern Christian kingdoms, that eventually played such an instrumental role in the dismantling of Umayyad and Arab power in the Iberian peninsula.

It is also notable that there were several “Slavic” (or Saqlabī) kingdoms that arose, since many of these “Slavs” (many of whom were actually Franks or Germans slaves or freedmen from Western or Central Europe) also played an important role as administrators and soldiers in the late Umayyad period. Although the two Arab kingdoms of Seville and Zaragoza were among the most extensive, stable and powerful, they represented a minority of the kingdoms and the fact remains that between roughly 1000 A.D. and 1220 A.D. (i.e. from the Taifa period to the devolution of the Almohad caliphate) al-Andalus would remain dominated by Berber polities. This fact, coupled with the reality that the vast majority of Andalusīs were Arabic-speaking Hispano-Muslims, Christians or Jews contributed to the emergence of a distinct political system in which Berber political and military rulers worked alongside local Andalusī administrators, fiscal agents and elite families. For more on the complex and interesting socio-political dynamic of the Taifa period, here is a summary of Abdullah b. Buluggin’s Tibyān: https://ballandalus.wordpress.com/2014/02/15/the-tibyan-of-abd-allah-ibn-buluggin-r-1073-1090-a-fascinating-glimpse-into-the-world-of-eleventh-century-iberia/ ). The following are the main kingdoms that existed in al-Andalus between the fall of the Umayyad caliphate in 1013 and the Almoravid conquest in 1090:

Taifa de Albarracín (1011-1104). Ruled by the Hawwara Berber Banū Razzīn family

Taifa of Algeciras (1035-1058). Ruled by the Hammudids, who were a Berber dynasty that claimed partial descent from ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib (d. 661). They briefly claimed the caliphate following the fall of the Umayyad dynasty.

Taifa of Almeria (1011-1091). Ruled by various Saqlabī Muslim rulers until the Arab Tujibi Banū Sumadih took over in the 1040s

Taifa of Alpuente (1009-1106). Ruled by the Kutama Berber family of the Banū Qāsim

Taifa of Arcos (1011-1068). Ruled by the Zanata Berber family of the Banū Jizrūn

Taifa of Badajoz (1009-1094). Although founded by a Saqlabī Muslim (Sabur), it was ruled by the Miknasa Berber Banū Afṭaṣ family. It was one of the most powerful and extensive of the taifa kingdoms.

Taifa of Carmona (1013-1091). Ruled by the Zanata Berber Banū Birzāl dynasty

Taifa of Denia (1010-1076). Ruled by the Saqlabī Muslim Mujāhid al-‘Āmirī and his sons

Taifa of Granada (1013-109). Ruled by the powerful Sanhaja Berber Banū Zīrī family, who were originally governors for the Fatimids in Ifrīqīyah (modern-day Tunisia and eastern Algeria)

Taifa of Malaga (1026-1090). Ruled by the Berber Hammudid family before being seized by the Sanhaja Berber Zirid taifa of Granada between 1058 and 1090

Taifa of Majorca (1076-1116). Ruled until 1075 by the Saqlabī Mujāhid al-‘Āmirī and his son ‘Alī before being controlled by the Banū Aghlab family for the remainder of its existence

Taifa of Murcia (1011-1090). Although founded by a Saqlabī Muslim (Khayrān al-‘Āmirī), this kingdom was contested between various Saqlabī, Berber and Arab rulers in al-Andalus until it was finally integrated into the Almoravid polity. However, during the second and, especially, the third Taifa periods Murcia would be one of the most powerful kingdoms.

Taifa of Niebla. Founded and ruled by Abū-l ‘Abbās Aḥmad b. Yaḥya al-Yaḥṣūbī, descended from the notable Arab Muslim family of the Banū Yaḥṣūb, and his successors until it was conquered by the Banū ‘Abbād of Seville in 1053

Taifa of Algarve (1016-1052). Founded and ruled by the Hispano-Muslim Banū Harūn family until it was absorbed into the expanding ‘Abbādid taifa of Seville in 1052

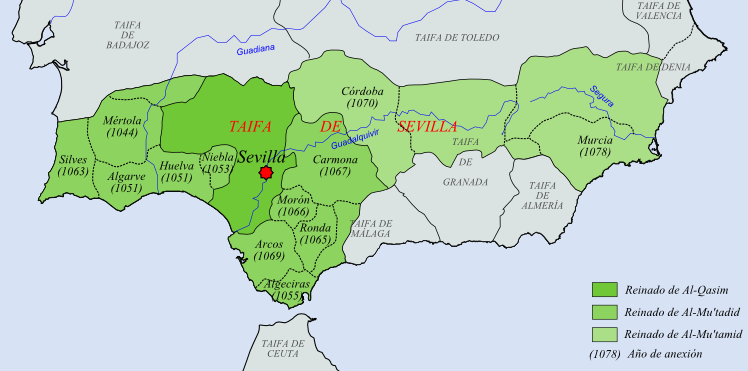

Taifa of Seville (1023-1091). Ruled by the Lakhmid Arab Banū ‘Abbād family until its conquest by the Almoravids. It was one of the most powerful and expansionist of the taifa kingdoms

Taifa of Toledo (1010-1085). Ruled by various individuals until the Hawwara Berber Dhū-l Nūn family took power in 1032 and controlled it until its conquest in 1085 by Alfonso VI of Castile

Taifa of Valencia (1010-1094). Ruled by the Saqlabī Amirid dynasty of Mujahid of Denia and his sons until it was seized by the Berber Banū Dhū-l Nūn dynasty of Toledo in 1085 (and the city was conquered by Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar or “El Cid” in 1094)

Taifa of Zaragoza (1013-1110). Ruled by two Arab families: the Banū Tujib (1013-1039) and the Banū Hūd (1039-1110). The descendants of the Banū Hūd would play a particularly prominent role in the second and third Taifa periods as well. The famous Sayf al-Dawlah (the Zafadola of the Castilian chronicles), whom I have written about elsewhere on this blog, was descended from this line.

(There existed other taifas centered around the towns of Cordoba, Lisbon, Ceuta, Lorca, Mertola, Ronda, Silves, Tortosa but these were very short-lived and fell under the domination of one of the larger and more powerful kingdoms by the mid-11th century)

(Map of the Taifa Kingdoms with the Berber dynasties shown in brown)

Further Reading

Travis Bruce. “Piracy as Statecraft: The Mediterranean Policies of the Fifth/Eleventh-Century Taifa of Denia.” Al-Masaq 22 (2010): 235–248

Abdullah ibn Buluggin. The Tibyan: Memoirs of Abd Allah b. Buluggin, Last Zirid Emir of Granada. Leiden: Brill, 1986. Translated by Amin Tibi.

Pierre Guichard and Bruna Soravia. Los reinos de taifas: Fragmentacion politica y esplendor cultural. Malaga, 2006

Andrew Handler. The Zirids of Granada. Miami, 1974

Goran Larsson. Ibn Garcia’s Shu’ubiyya Letter: Ethnic and Theological Tensions in Medieval al-Andalus. Brill, 2003

Peter Scales. The Fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba: Berbers and Andalusis in Conflict. Leiden: Brill, 1994.

David Wasserstein. The Rise and Fall of the Party-kings: Politics and Society in Islamic Spain, 1002-1086. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985

Comments